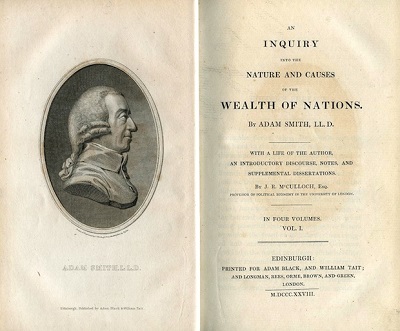

Two main reasons for studying economics are often given in textbooks and classes. First, it helps us understand the social world we live in and, secondly, it informs better public policy decisions. An example comes from Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations. By understanding what makes a nation wealthy compared to others, we might be able to develop a roadmap for other nations to reach prosperity too.

A less often discussed motivation for learning economics is for better personal decision-making. Economists use economic reasoning to make better decisions in their personal lives, but they don’t always propose this as a major benefit to their students or the public. This is possibly because economics is too often conflated with the study of finance or business; economic theory is not a series of recipes for making money. However, it can help students get a clearer idea of how to make the most of life.

There’s a kernel of truth in jokes about how it doesn’t take a genius to get rich. Here’s one:

At a 10-year high-school reunion, a middle school math teacher arrives in a beat-up old sedan and an old buddy of his pulls up in a shiny new convertible and all the trappings of wealth. The math teacher recalls that this friend barely squeaked by in his high school classes. “You seem to be doing well”, he says as he greets his friend, “what’s your secret?” The friend replies, “I just follow the 5 per cent rule. Buy something for $5, sell it for $10.”

It’s true, and likely a virtue of market economies, that individuals with little deep knowledge of mathematics or how the world works can amass wealth, yet it is more likely that wealth can be maintained with some understanding of economics. It is possible to have a high income, yet little actual wealth if that income is mismanaged, or if opportunity costs are poorly assessed.

Basic assessment of opportunity cost can inform financial decisions. For instance, it is almost always better to finance something over a period if 0% interest is offered. If you have to pay $1,200 now or $100 per month for 12 months at zero interest, the latter is a better deal, as long as there are no other significant transaction costs that come with that option. If you make payments on time each month while earning simple interest on the money in the bank, and assuming the interest rate is 5 per cent, you will earn around an extra $27 in interest that year. Therefore, you get what you bought and $27 (which would be greater with compounding). Lots of such decisions can add up, and every dollar counts.

A corollary of this is that making early tax payments is likely not worth it. If you get a big refund after filing your taxes, you overpaid during the year and have essentially lent your money to the government at zero interest for the period between your payment and receiving the refund. Individuals may feel frightened of having a big tax bill at the end of the year, which is understandable. One could take the money that you will owe to the government and put it in an interest-bearing account until the end of the year, then pay the taxes and keep the earned interest afterwards. The same example above applies here.

The “efficient markets hypothesis” developed by economist Eugene Fama implies concrete advice about investing in financial markets: diversify and minimize transaction costs, you don’t know more than the market (and professional portfolio managers don’t either). Economics proposes no “get rich quick” schemes, but it does have a “get rich slowly” plan.

To be sure, many economists explicitly provide economic lessons for better decision making. Justin Wolfers and Betsey Stevenson focus on it in their podcast Think Like an Economist, which is still worth listening to, although they stopped producing episodes a few years ago. Steven Landsburg offers usable insights in The Armchair Economist. Tyler Cowen provides advice for using economics in An Economist Gets Lunch and Discover Your Inner Economist.

Bryan Caplan, in his blogging and new book, Self-Help is Like a Vaccine, has employed theory and clear thinking to offer actionable advice about real issues that people care about. Many have attested to the value of his advice, and much of this essay has been learned from him through his writing and teaching.

Jane Austen reportedly said that “a large income is the best recipe for happiness I have ever heard of”. While funny and true, the law of diminishing returns suggests that beyond a certain level of income, an extra dollar will not get you much more happiness.

Economists know that money isn’t everything. It is a stand-in for control of resources and the power to live the kind of life that you want. If you can secure that life through non-monetary means, then it makes sense to do so. Of course, many people without formal knowledge of economics are already great at using such thinking to make life decisions, they just may be unaware that they are doing it.

Giorgio Castiglia is the Program Manager for the Project on Competition at the Mercatus Center, and a PhD student in economics at George Mason University.