The Economist has a recent article discussing a fascinating natural experiment:

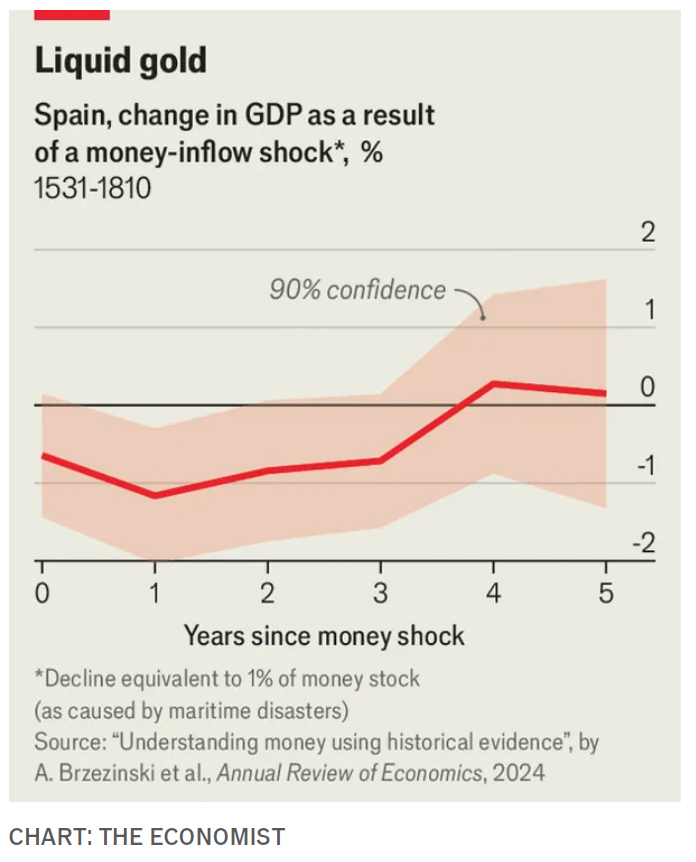

History does nevertheless throw up “natural” experiments. In an earlier paper, Mr Brzezinski, Mr Palma and two co-authors exploited one source of variation in the money supply of early modern Spain: disasters at sea. Ships carrying treasure to Spain from the Americas would sometimes encounter hurricanes, privateers or the British navy. In 42 incidents from 1531 to 1810, they lost some or all of the precious metals that Spanish merchants had expected to receive. The losses averaged 4% of Spain’s money stock. Drawing on a variety of sources, including tax records and tallies of sheep, the authors showed the damage these losses inflicted on Spain’s economy. Credit became scarce, making it hard for merchants to buy supplies for weavers, and consumer prices were slow to adjust. A loss of 1% of the money stock could reduce real output by about 1% in the subsequent year. Sheep-flock sizes fell by 7%.

Although I like this finding, a word of caution. The statistical significance of the study seems rather low:

If this study did not agree with my preconceived ideas about monetary shocks, I’d be telling you that it was just barely significant at the 90% level, and that this could easily reflect the tendency of journals to prefer studies that find a positive effect over those that find no effect at all. (I guess I did tell you that. :))

But for the moment, let’s assume that the finding is true; a loss of gold really did hurt the Spanish labor market. After all, we’ve seen many modern examples of negative monetary shocks resulting in higher unemployment, notably following significant declines in the US monetary base during 1920-21 and 1929-30. Why would this effect occur?

There is no obvious reason why Spain being a bit poorer should make Spanish workers wish to work less hard. If anything, you’d expect extreme poverty to be a spur to work harder, if only to avoid starvation. The real problem is that negative monetary shocks act as a sort of price control, they push an important market price out of equilibrium.

We normally think of disequilibrium prices as being caused by things like price controls, rent controls and minimum wage laws. Ryan Bourne recently edited an excellent book on this problem, which contains numerous case studies. But price regulation is not always the problem. Monetary policy instability can cause a similar problem. So can irrational public attitudes, such as opposition to “price gouging”, or money illusion.