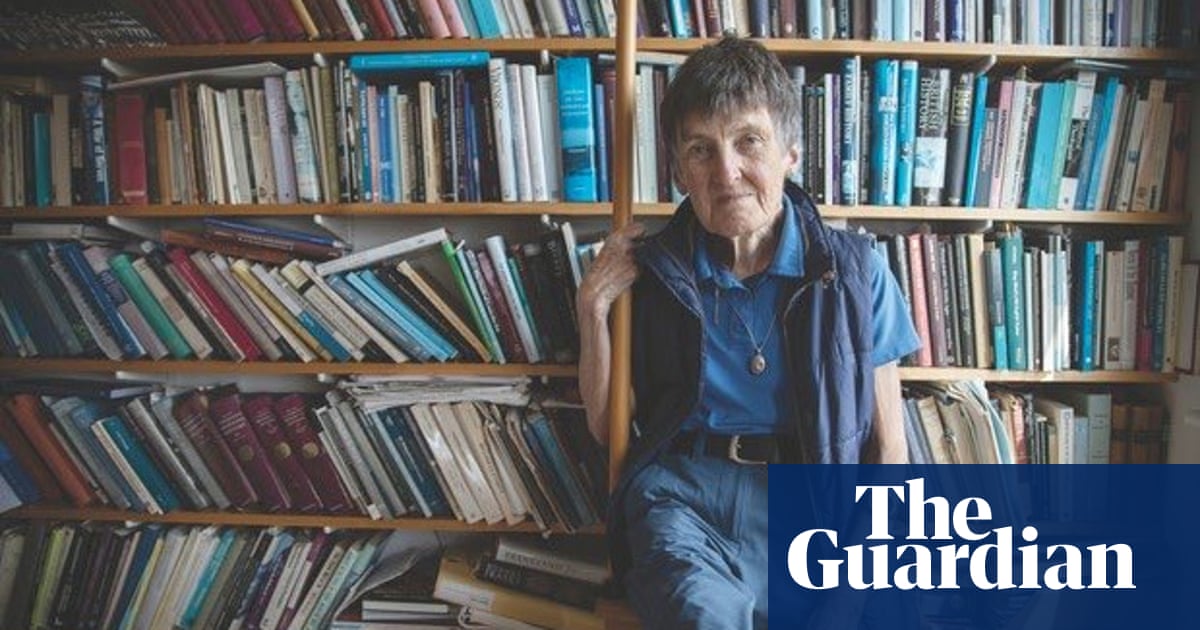

The medieval historian Janet Nelson, who has died aged 82, regarded the international exchange of ideas as essential to the understanding of history, and she was particularly concerned to counter the exceptionalism that has so often distorted each nation’s account of its past. Jinty, as she was affectionately known, managed to combine impeccable scholarship with a high degree of empathy towards figures past and present. It was this combination that made her work attractive to all comers.

She studied under Walter Ullmann at Cambridge University in the mid-1960s, and at first followed his interests in writing about early medieval inauguration ritual – the crowning of rulers – before broadening out to study the ways in which heresy was defined, and looking at how the elite were able to reinforce their standing by establishing family members as saints.

Later, however, she challenged Ullmann’s work head on. In common with most historians of the mid-20th century, he had a rather top-down constitutionalist view of how continental Europe developed in the early middle ages. His view of Charlemagne’s empire (from 800) was that it had a theocratic government strong enough to engender a cultural renaissance that would shape the Europe to come. That “renaissance” involved a reform of language, the setting up of schools and a return to classical forms of poetry, all folded into a programme of moral reform.

In one short, crisp paper, On the Limits of the Carolingian Renaissance (published in 1977 in Studies in Church History), Jinty argued that Carolingian government simply lacked the power to drive through such reforms. How could a government with limited means and little sophistication direct an ambitious cultural programme? How did Charlemagne actually govern? From this angle the so-called “Carolingian renaissance” could not be viewed as a decisive moment in European cultural and political development.

Jinty’s brief interrogation of a tried but tired narrative had a strong impact and helped kick off new interest in the extent to which the exercise of power actually affected people in pre-modern states. It is a mark of her commitment to understanding the issues rather than defending herself that Jinty came back to this subject many times over the years. While coming to appreciate the coherence of Carolingian thought, she also recognised that much of it was rhetorical. Carolingian ideas of morality bounded down the centuries, but they did not have power to change the nature of society. What she did think was that the Carolingian rulers did very well in creating a massive empire, given the limited means at their disposal.

Jinty was driven to understand lived experience, notoriously difficult to do for societies that thought, wrote and acted in ways that to us are as foreign as they are distant. She was nevertheless able to bring her sophisticated reading of lives to bear on women’s history and increasingly included gender issues in her analysis of power.

A stream of seminal papers followed in the leading historical journals of Europe and north America: on writing and gender, on widows’ inheritance strategies, queenship, women and royal courts, and the women in various royal families, not least the daughters of Charlemagne. Studying the lives of individuals led Jinty to ask whether it was possible to write biography for the early middle ages. The problem lay in the nature of the record, in religiously driven conventions and in hindsight both ancient and modern.

Her first biography, Charles the Bald, of the ninth-century king (823-877), was published in 1992, and set the record straight for a much-maligned ruler. Her second, King and Emperor (2019), on Charlemagne, was her last work. To this she brought her own experience and understanding of family dynamics. It was a result of 40 years of thinking. Made possible by a peerless reading of works in Latin, German and French, plus her legendary insight, it was a hard act for anyone else to follow.

In all Jinty published more than 140 papers, nearly all peer-reviewed. About half of them were gathered into four collected volumes: Politics and Ritual in Early Medieval Europe (1986), The Frankish World (1996), Rulers and Ruling Families in Early Medieval Europe (1999), and Courts, Elites and Gendered Power in the Early Middle Ages (2007). This was in addition to several edited works and a brilliant set of translations, The Annals of St Bertin, published in 1991 in the Manchester Medieval Sources series. Jinty co-founded this series, which has become a bedrock of research and teaching.

Of the many works she edited, one in particular shows her kindness and commitment. In Medieval Polities and Modern Mentalities by Timothy Reuter (2006) she gathered together and even finished off the papers of a colleague who had died mid career. Others, such as The Medieval World, edited with Peter Linehan (2001), have become library standards.

Jinty was born in Blackpool, the eldest of the three daughters of Scottish parents, Elizabeth (nee Laughland), who trained as a teacher before her marriage prevented her from working as one, and William Muir, a general practitioner. From Keswick school, in Cumbria, she went to Newnham College, Cambridge, to study history.

There she met Howard Nelson, an anthropologist specialising in Chinese culture, whom she married in 1965. Jinty briefly served in the Foreign Office before being appointed in 1970 to a lectureship at King’s College London. An inspiring and generous teacher, she built up a strong cohort of research students there, of whom I was one. She helped to make London a centre of excellence for early medieval studies, and in 1993 became professor at King’s, remaining in the post until her retirement in 2007. In 1996 she was elected a fellow of the British Academy, going on to serve as the academy’s vice-president. In 2000 she was the first woman to become president of the Royal Historical Society. In addition she sat on the editorial boards of two of the major history journals. In 2006 she was made a dame.

She was a lifelong CND member and Labour voter, a generous supporter of good causes and a Guardian reader who wrote many letters to the newspaper. Having young children while trying to forge an academic career in the 1970s had not been easy, so when in her late 50s her grandchildren came along, Jinty rejoiced in them and was a most devoted grandmother. Despite having Alzheimer’s in the last years of her life she loved playing the piano, the beauty of nature, and reading and spending time with her loved ones.

Her marriage ended in divorce in 2010. She is survived by her children, Lizzie and Billy, and grandchildren, Eli, Ruth, Martha, Dorie and John-Paul, and by her sister, Christine.